“There is no movement gathered here, just a circle of friends who have long sought an outlet for their unconventional opinions and tastes and not finding one have agreed to devote themselves to a long-term publishing enterprise.”

Editors | November 2023

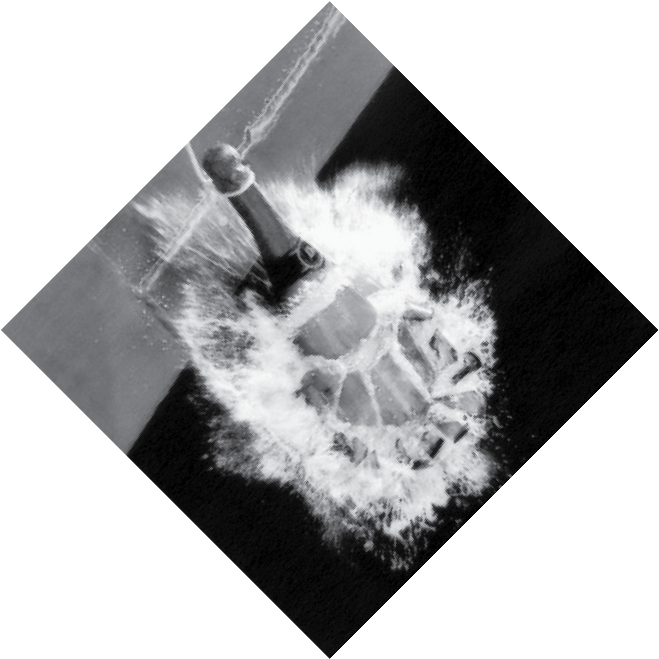

Boats have always been freighted with symbolic value. The ship of this journal’s title evokes an era before containerization. Its inaugural editorial plots a course through the origin story of the contemporary American Left. The contemporary in our view refers to a sequence of years following the first world economic downturn since the 1970s to put a question mark over the future of the capitalist system. A lot has been written about the financial crisis and its impact, but what follows will address certain subjective aspects of the political scene that arose as a response to it pertaining to the raison d’être of this publication.

Looked at from this subjective angle, the formation in question began with different, ideologically divided generations of the Left encountering each other and inadvertently forming a community of sorts. The latter would soon encompass countless, overlapping and competing circles, fluidly grouped around influential individuals offering occasionally distinct points of view and idiosyncratic opinions, some with allegiances to preexisting organizations and journals, but all made aware of each other’s existence through the social media platforms on which their crisscrossing disputes and alignments were staged in daily plebiscites. The core of these circles were often people who knew each other personally from one or another political or arts scene—mainly concentrated in a few cities in the US, the UK and Canada—but around these orbited assorted online allies and adversaries from all over the world. While this new mode of association widened some horizons, those who saw themselves as intellectuals tended to downplay the extent of their involvement as if embarrassed by the fact they were spending so much time in this ad-polluted, trivializing space. Among them, an anxious feeling of seeming a bit ridiculous was pervasive. Readers who passed through this milieu might nonetheless concur that a certain structure of feeling arose that would thoroughly envelop everyday life over the roughly dozen years that followed and reshape relations with nearly everyone they knew. As pirated intellectual riches poured online, a virtual public sphere took shape linking energetic protests to study groups and sympathetic classrooms—an expanding circuit that took on a strange life of its own for a time. An effervescent, floating realm. Many disparaged its theoretical culture and make-believe sense of agency, comparing it to pasts that they dimly recalled or had read about, but the younger cohorts that stood at its forefront occasionally exhibited an impressive appetite for texts from an ideological antiquity stretching back to the origins of the workers’ movement, as well as an undogmatic sense of the political relevance of these traditions.

Following the method of Alain Badiou’s The Century we could ask: what did this decade or so think? In other words, what was original in the most advanced thinking of these years that distinguished it from other, preceding times? On this score, skepticism towards an inflated sense of newness was warranted for its influencers tended to recycle the theoretical languages of the past as if unsure of the reality of the moment. Obviously, there was no collective subject to speak of here, but even in ideologically miscellaneous times a shared impulse to reject premises under which contemporaries had heretofore labored can sometimes emerge. What did this newly constituted sense of the present reject?

The hallmark prefix of the Left discourse of decades from the 1970s up to the period in question had been the “post”: post-Marxism, post-Fordism, post-modern, post-political, post-historical. The list is extensive, and taken together these terms form a recognizable gestalt. It was clear that something had shifted when all the micro-oppositional, deconstructive and plaintively messianic tones of this academic Theory discourse suddenly seemed embarrassingly passé. One could say the post received a kick from which it never fully recovered, though this intellectual change of scene was more sensed than remarked upon. Once proscribed terms like “subject” and “truth” resurfaced, expressing a desire to be taken seriously—a kind of “what is to be done?” outlook. At its height, the distinguishing common impulse of the thinking of this period was a desire to break with a discourse that testified to an exhaustion of possibilities. In its heady first years, many even felt comfortable denouncing the jargon of identity and victimhood—before the latter triumphantly returned in the final phase of this cycle, sweeping everything before it.

Bracketing these scattered novelties, the master concept of this moment, “neoliberalism,” was taken from the preceding period when it was already on its way to becoming ubiquitous. What did it now come to mean? Whereas previously it had signified a nearly unstoppable world market juggernaut, the financial meltdown of 2008 seemed to bring to the surface a fiery historical landscape of riots and rebellions, in a sort of apocalypse of neo-liberalism, its revelation as a deep, and possibly insurmountable structural crisis of capitalism. In a Pauline spirit, traditional, more exclusive notions of the working class as first and foremost an industrial formation were abandoned, and a new proletarian was identified that encompassed all those subject to the precarity of life under capitalism—the surplus laborer as the most abject figure of the lot, but closer to home, public school teachers, nurses, sex workers, and above all, graduate students—although just as before, not all would be equal under this new dispensation.

Johann Gottlieb Fichte, letter to Karl Leonhard Reinhold

“Whenever I have to witness the prevailing loss of any sense of truth and the current deep obscurantism and wrongheadedness, I am filled with a contempt I cannot describe.”

While this collective ferment felt almost historical, most intelligent participants could not shake the feeling that within its algorithmically-shaped dynamics of mass opinion formation and emoting the secret passages from virtuous activism to real praxis had been sealed. As in the past, high-spirited group think—to use the term without any pejorative connotation—had a tendency to slide into witless and cowardly mob behavior and from there descend into large-scale bouts of leaden depression before picking up again. And then the cycle came to an end, its spirit now hopelessly broken and dispersed. Currently the whole episode is fading out in the fog of post-pandemic physical and mental infirmity. Even before this depressive factor kicked in, most of those involved were in the mood to delete their memories of this transformative experience as the strange fabric of the personal relationships that made it up has in the meantime become the stuff of bitter recollection.

The willful forgetting of the experience of this period is a moment in a wider, ongoing transformation of the relationship of the oppositional to the establishment Left. From 2016 most of the scene described here had settled into a more pragmatic, electoral mode, as old and new revolutionary groupuscules disintegrated. The young democratic socialists who then came to the forefront mounted what then seemed like serious challenges to the leaderships of the parties of the Center-Left. With the collapse of these rebellions in the US as elsewhere in the West, the liberal establishment ceased to take seriously what remained of such left oppositions and unequivocally identified the populist Right as a more troublesome foe. Those who had hoped to change the system from within split into a majority that quickly accepted a supporting role in this new progressive front and a minority who vociferously reject the compromises of this unending come down. Clearly everyone involved has reasons for forgetting the alignments of the not-too-distant past.

The rise and fall of the electoral phase of this post-Occupy sequence must be seen in a broader context. The self-described anti-capitalism of the period from 2008 to 2016 (Trump) or, alternatively, 2020 (BLM, Biden) took shape just before the Western Center-Left became the unequivocally preferred party of capital, on the whole outstripping the Right in the extent of its support for the military, intelligence services and other pillars of democracy. While being the favored party of capital is not an unprecedented honor for parties on this side of the aisle, being the more aggressive proponent of war and domestic surveillance represents a significant departure from a pattern going back to at least WWII. In the light of recent experience, the contrarian element on the Left has concluded that the progressive mainstream has gone from being the consistently lesser of two evils to often being the worse.

What changed? In the salad years of nominally anti-capitalist protest, the more enlightened wing of the establishment had not yet taken full ownership of the Left’s historic rhetoric of race and gender, but it would soon come to deploy it ruthlessly in a formidable crusade against what it characterizes as a nearly fascistic right-wing populism. The apparent conviction behind the establishment’s embrace of demands to end what’s left of white supremacy and patriarchy has caught the more pliant majority of the Left off guard, not sure whether to be embarrassed or call out: “more please, sir.” More cause for forgetting.

Sociological transformations in the constituencies of the two wings of the political system underlie and reinforce these new lines of ideological struggle. Periodizing is hazardous and developments rarely fall into such neat plot lines. Perhaps the upheavals that burst onto the scene with the financial crisis simply interrupted, for a time, a longer-term realignment of Left and Right unfolding since the end of Communism. Thomas Piketty has identified the sociological basis of this in a migration of the old white working class to the parties of the Right, offset by a countermovement that has made the educated middle class the primary constituency of the Left. The symbolic adequacy of the Left-Right political spectrum has been once again thrown into question but this time without any prospect of the kind of post-ideological convergence or “third way” that had been foreseen in the 1930s, 1950s and 1990s. The political field is subject to a new kind of sharp Left-Right polarization even as the warring signifiers that buzz around these poles have shifted in accordance with the real and perceived interests of their main constituencies. In lumping in the malcontent Left with its main enemy, the progressive mainstream has effectively squeezed out any vantage point of critique.

What, then, is to be done? While many have taken note of this development, few have thought through its longer-term strategic consequences for they are indeed disconcerting. An uncompromising few once held that after the collapse of the workers’ movement, the animus now had to be principally directed at the Center-Left whose nostrums had come to dominate the intellectual sphere. “Fire for the Left, ice for the Right,” as one great intellectual memorably put it. But that was nearly a quarter century ago. Times have changed, and what remains of an older Marxist intelligentsia now flinches before a vociferous and feeble-minded progressive petit-bourgeoisie.

Historically, Marxism’s intellectual appeal—above and beyond any ethical concern for the oppressed and exploited—had always been its claim to embody the most advanced social and political thought of modern times. And it was this pretension of mastery that formed the main subjective condition of modern revolutionary politics. What would the workers’ movement have amounted to without works like Capital and all the other great writings it influenced and inspired? A passion for social justice would hardly have motivated the most gifted of the time to join its ranks. Even after this historic movement began its interminable decline, Marxism remained a place where the most ambitious intellectuals could still go to think along lines, to depths and on scales that were not otherwise attainable. To the extent that more than a few major thinkers could be found outside its ranks, and hostile to it, their accomplishments typically depended on the provocation the enemy perspective represented. The mass entry of intellectuals of the Left into institutions of higher learning from the 1970s introduced Marxism into whole new areas of inquiry, raising its historiographic and social-scientific standards of rigor as well as, in many respects, its philosophical and aesthetic culture. As everyone knows, this development changed the nature of Marxism as it moved further away from its political point of origin, but it should be noted that incorporation also kept this body of thought afloat at a time when everywhere outside the university it was being washed away. The academic Marxism of the English-speaking world was an improbably successful holding operation that is often taken for granted.

Academic Marxism is now coming to an end as its last great generation passes away. But its considerable accomplishments made possible the Occupy-era revival of Marxism. Given these relatively favorable conditions, why didn’t this scene throw up any new generation of ground breaking left-wing/ Marxist thinkers? The decisive variable can be isolated without difficulty: the cultural-ideological compulsions that govern the expression of opinion among the left-wing of the college-educated strata of incumbent and aspirant professions simply make this level of attainment impossible. While Marxists in the university have adapted, sometimes with mild dissent and anxious concerns about infantile excesses, those who truly despise the new conformity must tread carefully. Some readers will recognize this predicament, finding themselves in a zone where they must listlessly endure the intellectual and moral servitude that comes with not being able to speak and think with others without fear of censure or worse.

The sentiment is understandable, but so far the various attempts to explore the consequences of this predicament rarely rise above the polemical level and give little satisfaction to those who seek a more disinterested perch above the fray. When the intelligentsia was still a powerful force in politics, a few esprits fortes made the case for opting out; now that politics admits of no intelligent opposition, not many can summon up the strength of detachment. But a contemporary variant of ataraxia may prove useful for the spirit in the period we are heading into. For despite the collapse of the last “cycle of struggle,” the temperature is as high as ever in the wider body politic—here we speak of America—which though it knows no serious threats seems to be drifting into a pantomime of civil war and at the same time, perhaps, towards a military reckoning of the old-fashioned kind. A stasis reigns at the heart of this noisy storm, but throw in another economic slump and things will surely get chaotic. And yet no movement or party currently wishes to change anything significant—at least where we find ourselves—and this is likely to remain the case.

How can one begin such a movement? No one knows, obviously. The objective of this editorial is not to forecast the coming conjuncture nor to offer any strategic reflections on it. Compared to the politico-intellectual period discussed above and the ones that preceded it going back to the end of the Cold War, there’s currently little on offer in this regard, and for good reason: the historical disorientation is now far greater. A long period of drift has begun for those few—though they were a hardly inconsiderable number—who glimpsed in the rebellions described above the possibility of a politics speaking to the highest kind of intelligence and its associated modes of commitment. This journal is pitched to them.

“Not one of us, by means of what he can observe in the sphere of his own experience, can put together and reconstruct the law of the political universe in which he finds himself.”

Paul Valéry, “Crisis of IntelligencE”

Although some version of this classically Marxist nexus of history and strategy will be touched upon in the various pieces included in this first issue, many of them are written from perspectives wholly outside of this problematic and from across the political spectrum—extremes of Left and Right but much in between as well. The authors of the outlooks clustered here aspire to be unclassifiable although the reader will likely detect in their work the needle tipping to one or the other of the opposed poles. From a purely intellectual perspective, this classical division of political space remains un-transcended though no longer binding when it comes to determining which party in the domestic arena or which regime in the inter-state system should be judged the lesser of two evils. We see the main actors of our politico-ideological universe as black boxes.

The motivating idea for this publication is that the reconstitution of the plane of thought on which politics potentially becomes consequential is a more important task than trying to make the case from any currently existing ideological vantage point. Some here are of the view that the mind is simply more important than politics, and see the latter primarily as a means of securing the best conditions for the former. Others are even further removed and indeed hostile to the Left though respectful of its historic intellectual accomplishments. And the feeling from the other side is mutual, so we hope this journal will turn out to be a productive collaboration and find readers who are currently also without a political home. There is no movement gathered here, just a circle of friends who have long sought an outlet for their unconventional opinions and tastes and not finding one have agreed to devote themselves to a long-term publishing enterprise. Over the last several years it became apparent to us after many intoxicating exchanges at the editor’s residence and some nearby haunts, followed by bouts of text messaging between groups of two, three and more of us, that small group formation among those who delight in thought in all its forms is currently more important than activism or any other form of civic engagement. Currently little can be expected from such efforts. This journal will continue to be published for as long as this remains the case, and if things someday change in this respect, by that time the SS African Mercury may be sailing in a different direction.